| The

opening of the region to colonization created a demand for lumber destined

to the construction sector. Some of the region’s first inhabitants quickly

established small sawmills which produced wood used to build houses, barns,

churches and schools. The region’s first sawmills were in operation before

the 1920s. According to Father Zoël Lambert, who came to Hearst in

1920: “The first mill around here was built in McManusville (today, St-Pie-X)

by ‘old man Simmons’ (‘le vieux Simmons’). The mill was operated by only

one man. ‘Old man Simmons’ was owner, sawyer and everything in between.

It gave us a bit of lumber.” (excerpt from an interview with Mgr. Zoël

Lambert, Le Nord, September 1, 1976).

Meanwhile, Adélaïde Duguay recalls in an interview with Le Nord in 1977 that her husband, Charles, had worked at the McMechen mill during the summer that followed their arrival to Wyborn (which was then called Hazel) in 1915. (excerpt from an interview with Mrs. Adélaïde Duguay, Le Nord, July 6, 1977). Other small sawmills operated during the 20s, 30s and 40s in the Wyborn, Jogues, Halléwood (today, Hallébourg), Ryland, Lac Sainte.Thérèse and Mattice regions (click here for a list of these sawmills.) Many of these sawmills operated on steam engines activated by boilers, which were heated by burning sawdust. Mills were often located near a lake or a river to feed the boilers and for easier transportation of logs. Other small sawmills were activated by tractor engines. These

small sawmills were in operation for a few weeks up to a few months during

the year, either in the spring or the summer, and only employed a small

number of people, usually members of the family that owned the mill. During

the sawing period, people worked 10 to 12 hours a day, often six days a

week.

|

|

|

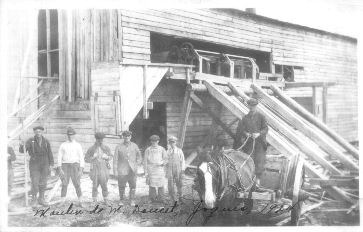

(Town of Hearst collection; picture donated by the Hearst Bishopric) |

| Wood

was taken on land owned by mill owners or settlers as well as on Crown

lands by virtue of permits granted to settlers. These settlers generally

harvested 100 cords of wood per winter.

Settlers brought logs to sawmills to have them transformed into construction wood, as recounted by Albert Dupuis who worked at his father Cléophas’ mill in Mattice during the 20s and 30s. “The

lumber we sawed was used to ‘build’ the settlers. They harvested their

wood, brought it to the mill, and we would saw it. In those days, we charged

eight dollars per thousand feet. The mill was something that was very good

for settlers. It helped them ‘build themselves’.” (Excerpt from an interview

with Albert Dupuis, from Gens de chez nous, Tome 1, page 130).

|

|

|

(picture donated by the Société historique) |

| During

the first years of these small sawmills, owners had no logging rights on

Crown lands (Noé Fontaine will be

the first one to obtain such rights in 1936). Licences to harvest timber

were instead awarded over vast territories (including entire townships)

to pulp and paper companies. At that time, government representatives argued

that these big companies had to be able to rely on immense reserves of

pulpwood. Such was the reason put forth to justify refusing to award small

local entrepreneurs the concessions they requested.

Even without licences to log on Crown lands, small mill owners actively took part in the lumber trade in the 1930s. Examples of these include Noé and Zacharie Fontaine in Mattice and the Bolduc family in and around Ryland. Established in Mattice in 1934, Noé and Zacharie Fontaine bought logs from settlers or obtained them in exchange for construction wood. Mr. Simon Nolet provided an example of such a trade involving the Nolet family of Mattice in 1934, whose house had just gone up in flames: “Over the course of the winter we had help to cut wood. Fontaine offered us help in sawing and transporting the logs. We paid him back for the sawing and the ‘planing down’ with more timber” (Excerpt of an interview with Simon Nolet, in Témoins de notre histoire, page 109). The Fontaines sold their wood to out-of-town buyers like Feldman Lumber of Timmins, mining companies of the same town and later on to southern wholesalers. The Bolduc family sold wood from their Ryland sawmill to the Guénette Company of Kapuskasing and to buyers from Southern Ontario. During the second half of the 1930s, certain mill owners like Noé Fontaine, Adélard Haman and Arthur Lecours managed to obtain logging licences on Crown lands. These licences enabled them to expand, while other small sawmills were gradually forced out of existence.

|