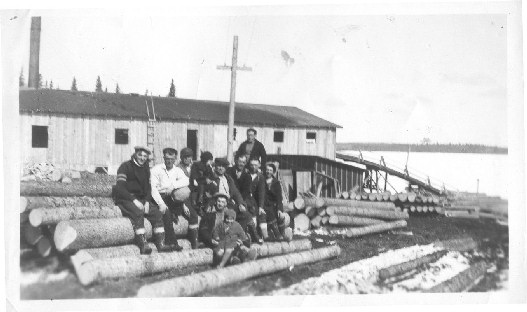

| The acquisition of logging rights on public and private lands by local entrepreneurs led to the development of the region’s lumber industry. In 1936, Noé and Zacharie Fontaine were the first lumbermen in the region to obtain a logging licence on Crown lands, more precisely in the township of Hanlan. This led to the construction of the Fontaine's Landing sawmill, as well as camps and other buildings necessary for its operation. |

|

|

(Écomusée de Hearst et de la région collection; picture donated by Mr. René Fontaine) |

| In

1938, Adélard Haman obtained logging

rights in Stoddard Township and built a sawmill near Carey Lake. A few

years later, Arthur Lecours built a sawmill

and a planer nearby, which was sold to Ernest

Gosselin in 1944.

Some entrepreneurs negotiated logging rights from pulp and paper companies that harvested pulpwood in the region. Rosaire Lecours (Arthur’s brother, nicknamed “Fred”) obtained logging rights in Studholm Township from Arrow Timber, an American company, and in 1942, he built a sawmill near Angelina Lake (in front of Forde Lake.) Others

obtained logging rights on private townships belonging to the Transcontinental

Timber Company (bought out by Domtar in the 1970s.) It is notably the case

of Willie Létourneau and his mill near

the Kabina River, which he sold to J. D. Levesque

in 1948.

|

|

|

(picture donated by Mrs. Rita Lecours) |

| In

1948, Henry Selin, a Swedish entrepreneur, established

a sawmill and a forestry village at Nassau Lake after obtaining substantial

logging rights on Transcontinental Timber’s private townships.

Levesque and Selin were unsuccessful in their bid to secure logging rights on Crown lands, with representatives of the Department of Lands and Forests arguing that wood was not in sufficient supply due to exploitation by pulpwood-exporting companies. During the early 1950s, after lobbying Ontario’s Conservative Government, J. D. Levesque obtained a logging licence in the Ritchie Township. This new development led to the establishment of J. D. Levesque’s sawmill in this township in 1953. The first logging concessions granted to local sawmill entrepreneurs were small, thus creating precarious viability for young lumber enterprises. J. D. Levesque, for example, had a mere 9 000 cords licence for his Ritchie mill, which was very little to fund the construction of a road and a forestry village (Excerpt from an interview with Roland Cloutier.) Furthermore, small lumber enterprises are denied loans from financial institutions. They are funded by wholesalers from Southern Ontario who offer them advances on their purchases of lumber, but also retain a large portion of the profit margins. At that time, most sawmills operated on a seasonal basis mainly due to an insufficient supply of timber. The Fontaine mill in Ryland functioned during the winter while the Fontaine mill at Lac Sainte.Thérèse operated only during the summer. Levesque’s Kabina and Ritchie sawmills both operated only during the winter, with a seasonal production of roughly fifteen million feet of wood. In comparison, the Henry Selin Forest Products mill, which benefited from a large enough supply of wood to operate year-round, produced 25 million feet of wood in 1952 alone (Excerpt of an article from “Serving the North”, November 1952). To increase revenues, mill owners used smaller logs to make pulpwood which they sold to pulp and paper companies. Meanwhile, pulp and paper companies got involved in lumber production during the 1940s and 1950s to process larger logs. For example, the Marathon Paper Mills Company asked local people to install and operate sawmills on the company’s logging lands. Philippe Buteau, Albert Dupuis, Wilfrid Lallier and Henri-Louis Gosselin operated such sawmills, and were paid for every thousand feet of wood they produced. Meanwhile, Canada Forwarding, another pulp and paper company, purchased Adélard Haman’s Carey Lake mill and logging lands in 1945 and operated it until 1948, when the company left the region following a decision by the provincial government to outlaw the exportation of crude pulpwood outside of Ontario. This new measure was intended to force companies to transform pulpwood locally in order to generate more employment. Some companies attempted to bark their wood before shipping it out of the province, but this proved to be unprofitable. Pulpwood companies therefore gradually left the area. Their departure marked a turning point in the history of the Hearst region: local lumber entrepreneurs now had access to large logging territories. The lumber industry was thus allowed to expand and become the region’s main economic engine.

|